Specialist Advice — 14 minutes

Screening for STBBIs – which test should you take?

Screening for sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) is never trivial. The reasons for taking this step may vary depending on the intensity of sexual activity, risky behaviours or suspicion of infection following the appearance of various symptoms, for example. A targeted search may be sufficient, or it may need to be more comprehensive to ensure good results. How do you know what types of tests health care professionals recommend for your situation?

Certain STBBIs on the rise in Quebec

More than 40,000 people in Quebec receive a positive STBBI result each year. Of those cases, chlamydia is up 19% since 2014. Gonorrhea diagnoses have more than doubled in the same period. And lastly, cases of syphilis and lymphogranuloma venereum are on the rise again, whereas they seemed almost eradicated in the late 1990s.[1]

On the other hand, hepatitis and HIV diagnoses have declined since 2014. Nevertheless, the number of cases is still substantial (for hepatitis C, 1,300 cases were counted in 2018) and weighs heavily on the health network.[2]

The importance of screening

In 2018, half of the new HIV cases reported in the province were diagnosed late and, therefore, at an advanced stage of the disease. In addition, test results have sometimes revealed an accumulation of STBBIs in the same person. Such situations inevitably lead to greater difficulty in treating and curing the patients and increase the strain on a health care system already under tremendous pressure due to COVID-19 cases.[3]

To a lesser extent, for more benign STBBIs, late screening still multiplies the risk of contagion between partners. It also increases the likelihood of long-term consequences.

Screening is still one of the best ways to prevent the spread of STBBIs and increase the chances of recovery.

Who is most at risk of contracting an STBBI?

According to the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ), young people aged 15 to 24 years are at greater risk. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are also particularly affected by STBBIs.

Finally, the prison population, people who use drugs (mainly by injection) and sex workers are most likely to have an STBBI. This is also the case for people living in regions of Canada that are underserved by health services.[4]

Studies show that MSM represent a significant proportion of the population affected by STBBIs, particularly the most serious ones, such as HIV and hepatitis C. They are also affected mainly by syphilis and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Injection drug users are mainly affected by hepatitis C and HIV. In this case, sharing dirty needles is the main risk of infection, so prevention efforts must be directed toward providing sterile equipment.[5]

The following habits can significantly increase the chances of contracting an STBBI:

- Using drugs (not necessarily injectable) or alcohol, which can impair judgment and increase risk-taking

- Having unprotected sex and multiple partners during sex or over a short period

- Getting tattoos under unsterile conditions

There are also risk factors that are not inherent in the behaviours, such as the following:

- Having contact with a dirty needle (in a professional or non-professional setting)

- Having blood or tissue transfusions

- Being the victim of sexual assault[6]

What tests should be performed based on the risk factors?

The Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) has prepared and published a table indicating the chief risks of contracting one or more STBBIs and the recommended tests based on those risks. You can choose the appropriate screening based on the risks involved by referring to it.

Refer to the table of STBBIs to look for according to the risk factors identified (French only).

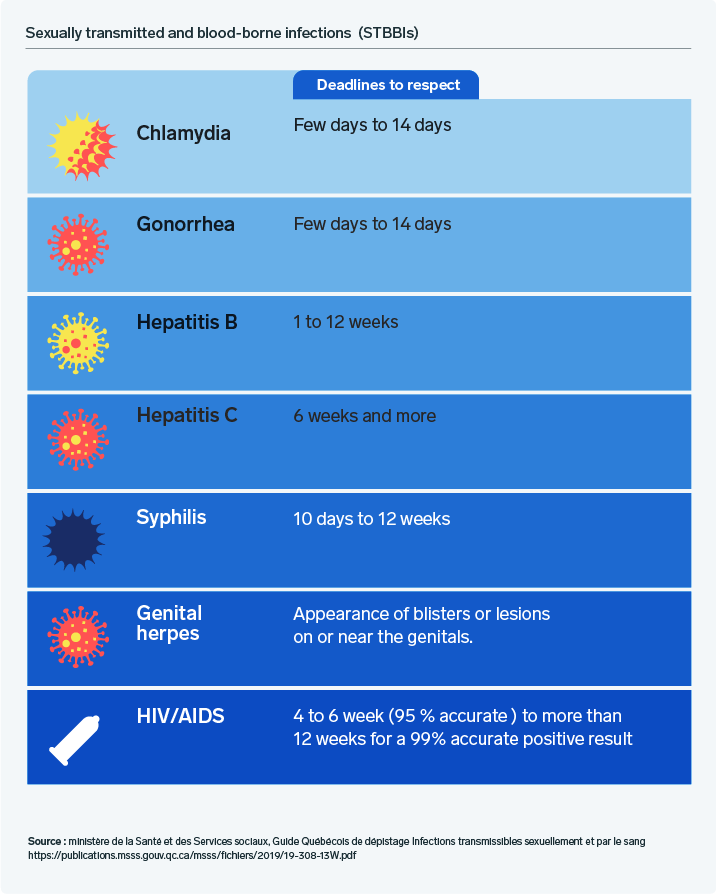

What are the testing timeframes for each infection?

People may consider a one-time test when they believe they have recently engaged in risky behaviour or suspect a possible infection. In such cases, there is no point in rushing to a medical clinic within the first week (unless there are specific symptoms). Infections usually take several days to develop and become detectable through screening.

In some situations, it is possible to take preventive measures (for example, when you come into contact with a dirty needle). Therefore, it is vital to speak to health care specialists or your family doctor promptly if you are unsure.

In some situations, it is possible to take preventive measures (for example, when you come into contact with a dirty needle). Therefore, it is vital to speak to health care specialists or your family doctor promptly if you are unsure.

For professional support, we’re here.

We provide a wide range of services related to HPV and other STBBIs. Test results for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, hepatitis B and HIV are available within 24 hours. A doctor's prescription is required.

Do you have a medical prescription for any of these tests? Book an appointment online or contact Biron Health Group’s customer service at 1 833 590-2712.

Sources3

- [1] Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (2018). Sexually transmitted infections and the sexual health of Quebecers in a few figures (free translation). https://msss.gouv.qc.ca/professionnels/statistiques-donnees-sante-bien-etre/flash-surveillance/itss-et-sante-sexuelle-des-quebecois/

- [2], [3], [4], [5] Institut national de santé publique du Québec (2018). Profile of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) in Quebec: 2018 and 2019 projections (free translation). https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2612

- [6] Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (2014). Quebec guide to screening for sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (free translation). https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-000090/