Specialist Advice — 12 minutes

Demystifying the “war on sugar”

March 17, 2025

“Cut out sugar!”

Now that’s something we hear all the time, as if it were the solution to all our health problems. Sugar is undeniably at the heart of many debates and is often singled out as the cause of chronic disease, weight gain and even addiction comparable to that of cocaine.

But is sugar really the number one enemy we need to wage an all-out war on? Before demonizing it, let’s take a moment to understand its role in our diet and demystify exactly what the “war on sugar” is.

But is sugar really the number one enemy we need to wage an all-out war on? Before demonizing it, let’s take a moment to understand its role in our diet and demystify exactly what the “war on sugar” is.

The start of the war

The idea that we should “wage war” on sugar is not new. In the late 1950s, growing concern over cardiovascular disease sparked a surge in nutritional research, giving rise to major debates among experts [1]. Two schools of thought clashed. One research group, under the influence of American physician-physiologist Ancel Keys, targeted fat as the main cause of health problems. Whereas, an opposing approach, led by British nutritionist John Yudkin, blamed sugar [2].

This clash between two clans, one waging war on sugar and the other on fat, marked the start of a long battle over the effects – sometimes proven, sometimes not – of the various nutrients found in food. Although the war has remained in the collective imagination, the research has evolved.

A revised war

Today, research is no longer satisfied with singling out sugar. Now, researchers are interested in the overall quality of the food we eat, the different types of sugar they contain, and the complex interaction of these elements in our diet [3]. This change in perspective enables more nuanced analyses, better adapted to our reality, and helps us better understand sugar in all its forms. Let’s explore its many facets!

Understanding sugar to make the right choices

Explaining what sugar is, is a little more complex than simply saying “sugar”. The term actually encompasses several types of carbohydrates, each with different characteristics and effects on our body [4].

Sugar can occur naturally, as in fruits and vegetables (in the form of glucose, fructose and sucrose) as well as in dairy products (in the form of lactose). These different types of sugars are not considered added sugars, since they are part of the food in its natural state, often with other nutrients that are good for our health.

When we use the term “added sugars”, we are referring to sugars that do not naturally occur in foods, but are added during the manufacturing process, to improve their taste, texture or shelf life. Common sources of added sugars include, for example, table sugar (sucrose), honey (glucose and fructose), maple syrup (sucrose, glucose, fructose) and high-fructose corn syrup (glucose and fructose) — for further clarification, see the Additional Information at the end of this article.

Fruit puree, such as date puree, can sometimes also be considered as an added sugar when it is used to sweeten processed products or recipes, even if it comes from a food that naturally contains it.

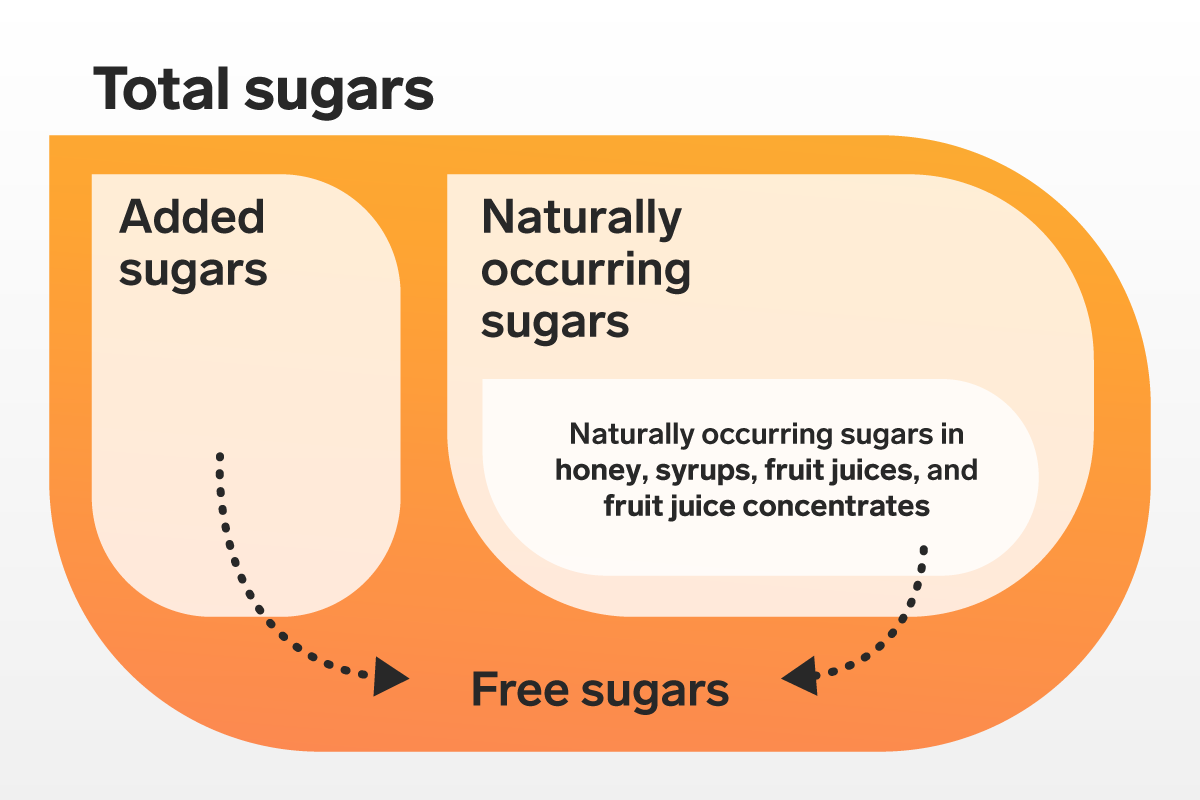

Total sugars: Total sugars encompass all sugars found in a food, including both naturally occurring sugars and added sugars.

Naturally occurring sugars: These sugars occur naturally in foods, like those found in fruit, vegetables and dairy products.

Added sugars: These sugars are added to food during preparation, processing or at the table. They include white sugar, brown sugar, honey, agave syrup, maple syrup and corn syrup.

Free sugars: Free sugars are sugars added to food and drinks, and those naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juice and concentrated fruit juice. However, they do not include the sugars contained in whole fruit, vegetable and dairy products, as these contain fibres or proteins that slow down their absorption. Since free sugars are quickly absorbed by the body, they result in a more rapid rise in blood sugar levels and can have a more direct effect on metabolic health.

How to identify added sugars

Fortunately, there are a number of tools available to help us identify added sugars in food.

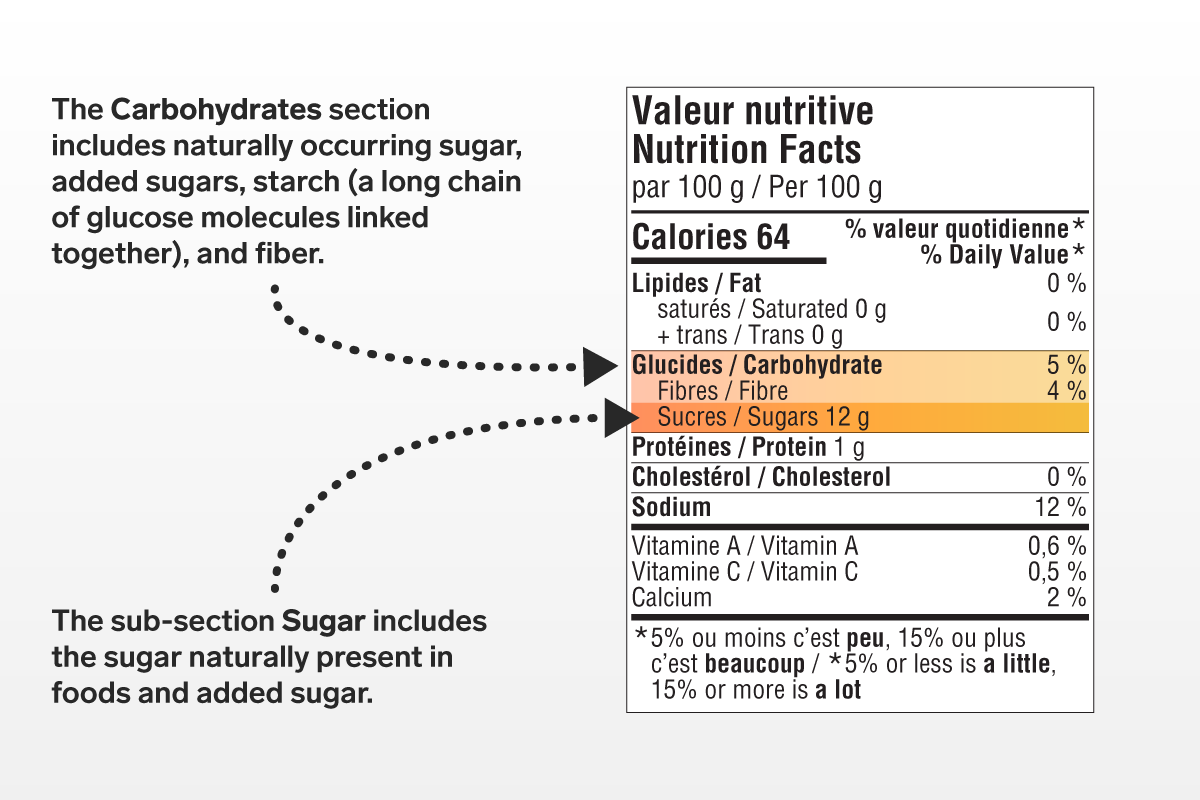

First, the nutrition facts table shows us the total amount of sugar per portion. But be careful: it doesn’t differentiate between naturally occurring sugars, such as those found in fruits, and added sugars. Although this information is still useful, it is important to look at the list of ingredients to see which sugars have been added. If you see terms like “sugar”, “corn syrup” (or “high-fructose corn syrup”), “honey” or “maple syrup” among the top of the list, this indicates that the product contains added sugars. The higher an ingredient is placed at the top of the list, the greater its quantity in the product.

Beginning January 1, 2026, a nutritional symbol will appear on the packages of certain products [5]. This symbol will indicate whether the food is too high in saturated fats, added sugar or sodium. This will help us to quickly and easily identify products that are too high in added sugars, making our choices simpler and more informed.

Marketing claims about sugar

Another aspect that should be addressed is marketing claims on packaging, which highlight certain product characteristics to attract consumers’ attention [6]. When a food is labelled “sugar-free” or “zero sugar”, this means that it contains little or no added sugar. However, this does not mean that it is completely sugar-free, nor that it is necessarily more nutritious. These products may actually contain sweeteners, substances that provide a sweet taste without calories. For example, some foods contain stevia or aspartame.

Even if a product is labelled “no added sugar”, this does not always guarantee that its nutritional value meets our expectations. This is why it is important to read the entire label, including the list of ingredients, to know exactly what you are consuming.

Added sugar itself is not poisonous, but if we consume too much of it too often, it has negative effects on our health [4,7]. Consuming too many added sugars has been directly linked to an increased risk of cavities in children. In young people and adults, it can also lead to an overconsumption of calories that exceeds the body’s real needs. In the long term, an excess of added sugars is associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, certain forms of cancer, metabolic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease.

Understanding added sugar recommendations, in teaspoons

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Health Canada recommend limiting added sugars to less than 10% of our daily calories, and even 5% for even greater benefits [7-8]. However, since these percentages can be complicated to understand, let’s look at them in teaspoons of sugar.

For example, for a person who eats around 2,000 calories a day, this is equivalent to approximately 50 g of added sugar, or 12 teaspoons. If we are aiming for the 5% recommendation, this represents 25 g, or 6 teaspoons of added sugar per day. One can of soft drink or soda, for example, can contain up to 40 g of added sugar, nearly the entire recommended amount for the day. This is why some experts are in favour of a tax on these products.

A flexible view of added sugars

It is important to recognize that added sugars can be useful in some contexts. When you do want to consume them, you should take a well thought-out approach to incorporating them into a healthy diet. For example, athletes may need fast-absorbing carbohydrates before, during or after exercising to improve their performance and recovery [9]. Similarly, after surgery, during illness or in cases of malnutrition, sugar may be needed to ensure adequate energy intake and help with recovery. Finally, we shouldn’t forget that small indulgences, such as an occasional dessert or candy shared with the family, are part of life’s pleasures and should not be associated with this “war”.

Everyone is talking about intestinal microbiota, and some argue that sugar may upset its balance. It is a rapidly evolving area of research: initial studies suggest that a diet rich in added sugars may affect the intestinal microbiota, but many questions remain unanswered. [10]. What we do know is that the effect of sugar varies from person to person, and that it is influenced by factors such as genetics, lifestyle and overall diet. Even if an excess of added sugar seems to promote the growth of certain harmful bacteria, it is still too early to draw any definitive conclusions. Nevertheless, this field of research is evolving rapidly and may help shape health recommendations in the future.

Making peace with the “war on sugar”

Now that we have a better understanding of sugar, and realize that it’s not all black and white, it’s clear that talking about the “war on sugar” leads to a negative view of nutrition. Instead of demonizing all sugars, it is better to adopt a more nuanced and positive approach.

Saying “war on sugar” lumps all sugars together, whether they occur naturally in foods or are added to them, and this in turn fosters an immensely guilt-ridden vision. Of course, this type of talk attracts clicks on social media because it’s sensationalist! But this can lead us to adopt restrictive behaviours that are difficult to maintain in the medium or long term. The official recommendation is not to completely eliminate sugar, but to limit excess added sugars, while eating a varied, balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables (i.e., sugars that occur naturally in foods).

And we mustn’t forget: a kinder, gentler approach helps us improve our relationship with food and make healthy, sustainable food choices. That’s why we need to stop saying that we are waging “war on sugar”!

Additional information

Refined and unrefined sugars: Table sugar (sucrose), cane sugar (sucrose, often unrefined or partially refined), beet sugar (sucrose, similar to cane sugar, but derived from sugar beets), coconut sugar (mainly sucrose, with a little glucose and fructose), rapadura/panela/jaggery (unrefined sucrose derived from cane sugar), molasses (residue of sugar refining; contains sucrose, glucose and fructose with minerals).

Syrups and liquid sweeteners: Honey (glucose and fructose in variable proportions depending on floral origin), maple syrup (sucrose, glucose, fructose, with traces of minerals), high-fructose corn syrup (glucose and fructose, often in variable proportions; used mainly in soft drinks and processed products), corn syrup (mainly glucose), agave syrup (mainly fructose, with a little glucose), brown rice syrup (maltose and glucose; derived from hydrolyzed brown rice), date syrup (mainly fructose and glucose; derived from crushed and filtered dates), sorgho syrup (similar to corn syrup, but derived from sorgho; contains glucose and fructose).

Sugars derived from hydrolyzed starches: Dextrose (pure glucose, often derived from corn or wheat, used in food and pharmaceutical industries), maltose (two molecules of glucose; often derived from hydrolyzed starch, used in syrups and beer), maltodextrin (short-chain glucose, often added to processed foods as a thickener or mild sweetener).

Other natural sweeteners used as added sugar: Concentrated fruit juice (mainly fructose and glucose, often used as a natural sweetener in processed foods), lucuma powder (natural sweetener derived from lucuma fruit; contains glucose and fructose, but with a much lower glycemic index), yacon powder (mainly fructooligosaccharides, which may have a prebiotic effect and lower glycemic index), date puree (rich in fructose and glucose, often used in processed foods as a natural sweetening alternative).

Sources10

- “WHO’s war on sugar”. The Lancet. 2016;388(10055):1956.

- Yudkin, John, 1910-1995. (1972). “Pure, white and deadly: the problem of sugar”. London: Davis-Poynter Ltd.

- 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Dietary Patterns Subcommittee. “Dietary Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review”. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; July 15, 2020.

- Institut national de santé publique (2017). “La consommation de sucre et la santé” [Online], Gouvernement du Québec https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/2236_consommation_sucre_sante_0.pdf. Consulted on February 26, 2025.

- Health Canada (2025). “Front-of-package labelling awareness messages” [Online] https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/front-of-package-labelling-awareness-messages.html. Consulted on February 24, 2025.

- Health Canada (2024). “Nutrition labelling: Nutrition claims” [Online] https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/nutrition-labelling/nutrition-claims.html. Consulted on February 24, 2025.

- Health Canada (2022). “Sugars: Sugars and your health” [Online] https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/nutrients/sugars.html. Consulted on February 24, 2025.

- World Health Organization (2015). “Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children” [Online] http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/149782/1/9789241549028_eng.pdf?ua=1.Geneva: World Health Organization. Consulted on February 24, 2025.

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. “American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and Athletic Performance” [correction published in Med Sci Sports Exerc. Jan. 2017;49(1):222].

- Ramne S, Brunkwall L, Ericson U, et al. “Gut microbiota composition in relation to intake of added sugar, sugar-sweetened beverages and artificially sweetened beverages in the Malmö Offspring Study”. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(4):2087-2097.